Soot Tile Challenge

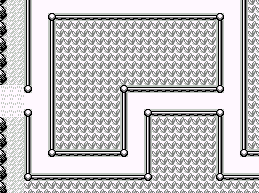

If you've played Pokemon Ruby/Sapphire/Emerald, then you'll remember Route 113, a route that had grass covered in soot. Each time you walked through one of these soot-covered grass tiles, you would collect 1 soot and the soot would disappear from the tile. When I was a kid, I enjoyed walking through the grass patches. I liked challenging myself to see if I could touch every tile exactly once.

As an adult, I learned more about concepts from math. Particularly, graphs. I began wondering if there was a way to tell in advance if a patch of grass could be walked through so you only touched each tile exactly once. How many of the grass patches in Pokemon Emerald could you walk like this?

I thus set out on this journey - to look at the grass patches on every route in Pokemon Emerald and figure out if you could walk them through exactly once, or if it was impossible to do so.

Background

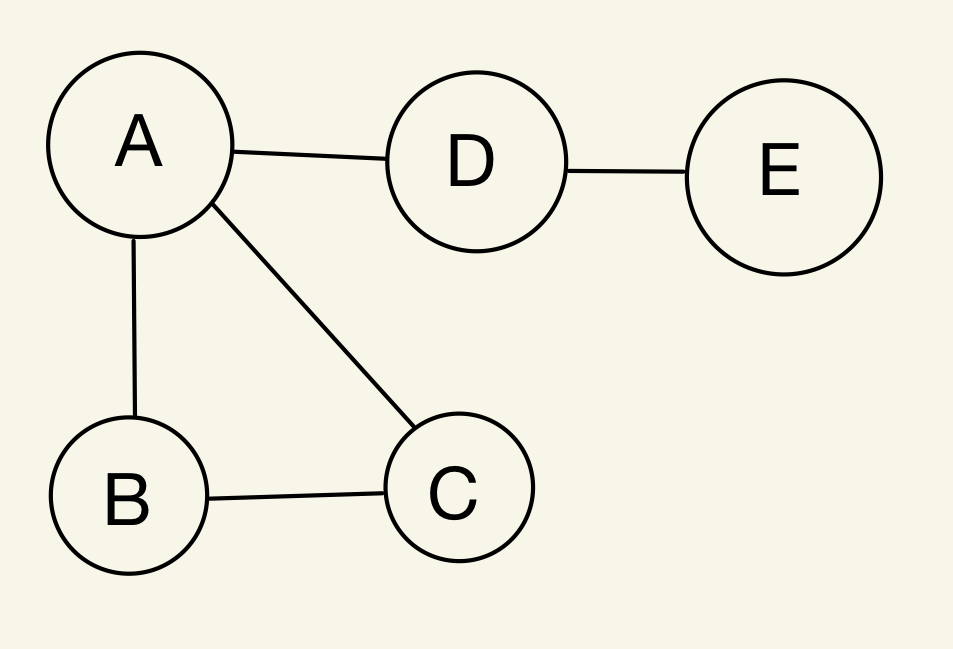

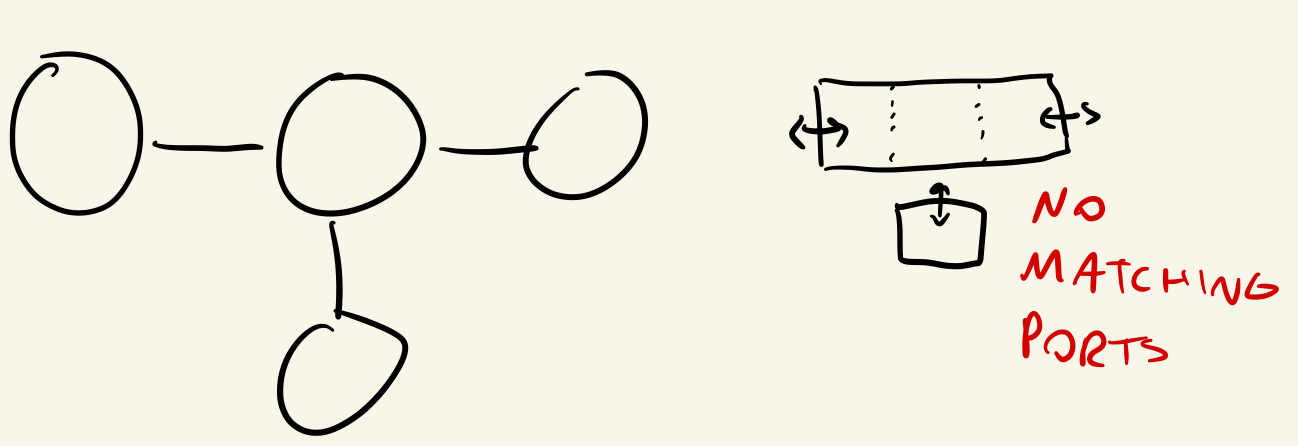

If you don't know what a graph is, here is a quick introduction. A graph is defined as a set of nodes. These nodes can connect to each other, and the connections are called 'edges'.

For example, in the image above, the nodes are labeled A, B, C, D and E. A and B are connected, which means there is an edge between each other.

It sounds simple, but graphs are very powerful tools for analyzing how systems are connected and how to move through them. For example, you can model friendships in a graph, where every person is a node, and friendships are edges between them. You can then run analyses to find out who has the most friends, the shortest path between any two people, and the people who are the farthest apart. In our image, you can see that A, B, and C are friends with each other, while E isn't friends with any of them.

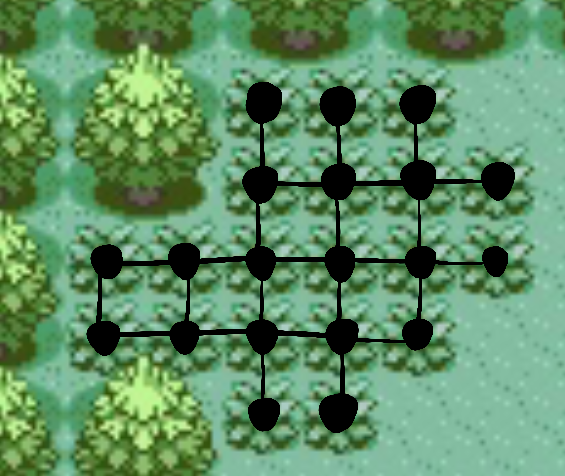

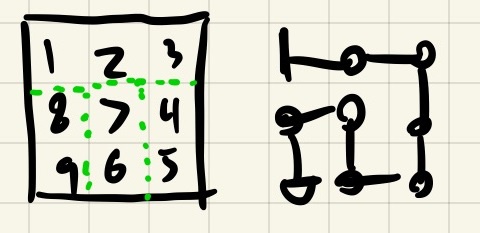

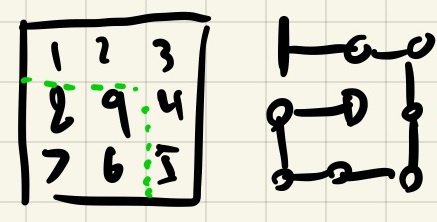

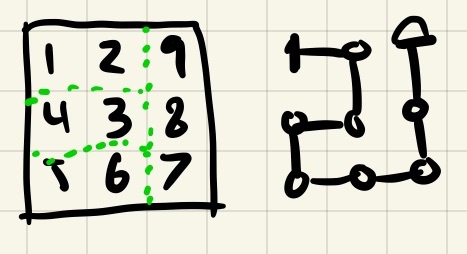

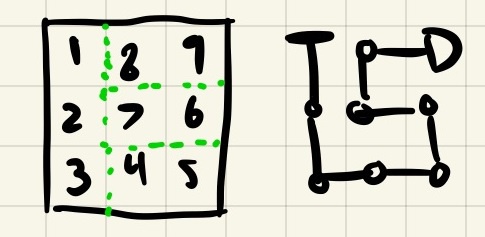

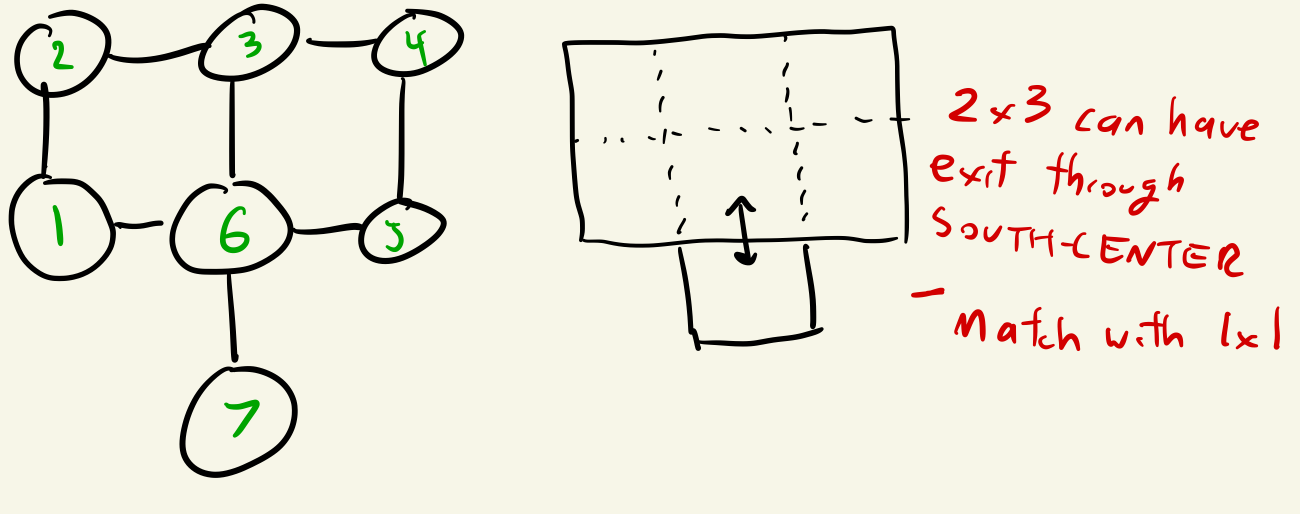

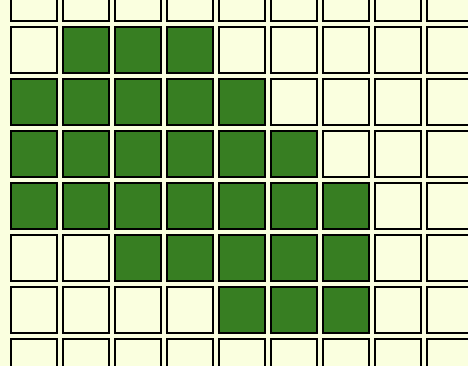

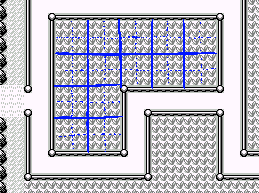

We can also imagine our grass patches as a graph! Imagine every tile is a node. In Pokemon Emerald, you can only move north, south, east, or west - there is no diagonal movement. This means that every tile has a maximum of 4 edges to 4 different tiles. You can see what that looks like below:

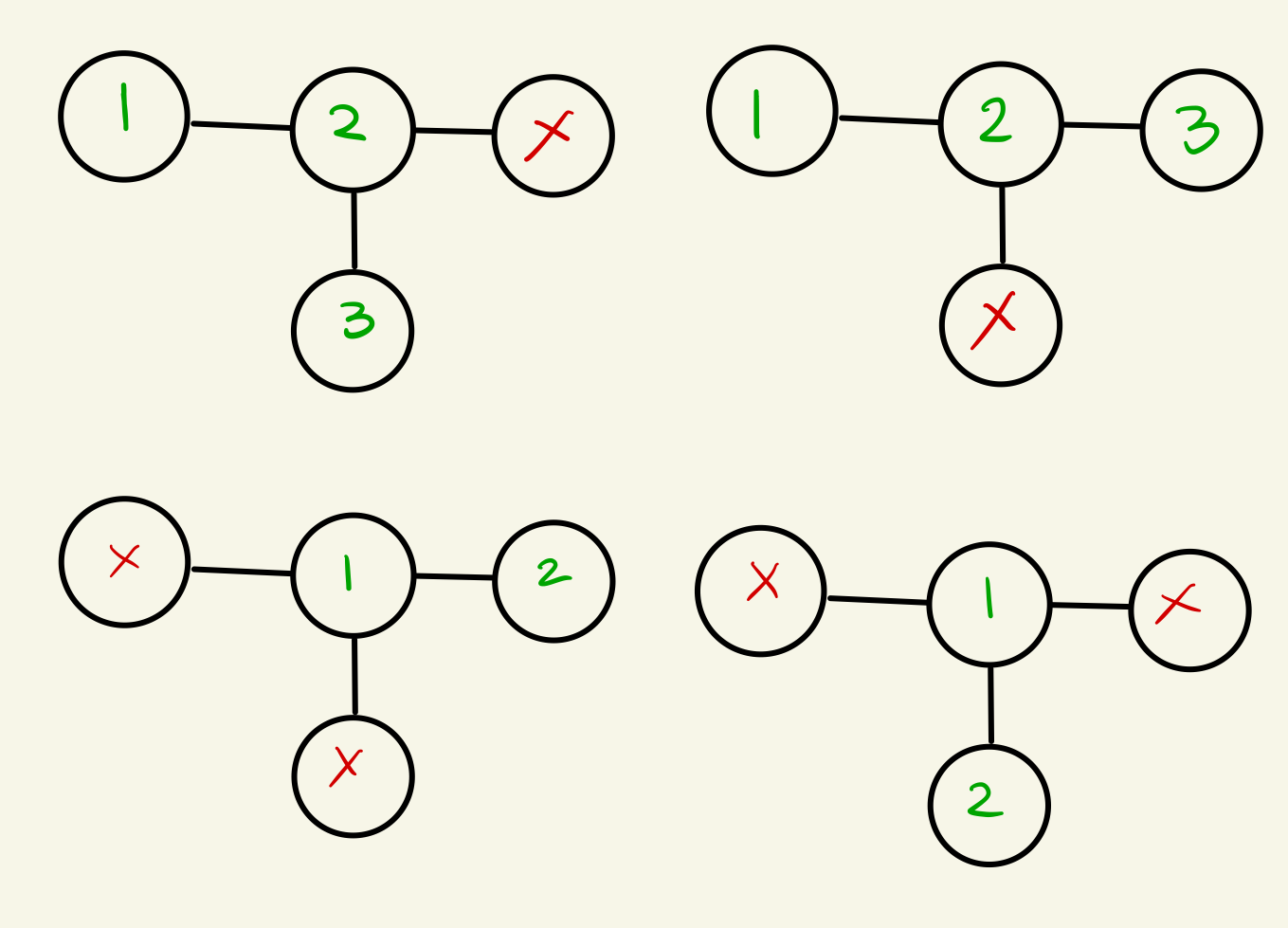

So, what we want to do is visit every node exactly once. If you want to read more about it, this is called a "Hamilton Path"! I want to keep things brief, so I'm going to refer to patches where you can walk through every tile once as "solvable" and ones where you cannot as "unsolvable."

I'm also going to add some game-specific conditions here. In the games, you can't just spawn in the middle of a grass patch randomly. There may be objects or walls preventing you from starting at a certain grass patch, or which prevent you from jumping directly to those patches. This means when I'm looking at grass patches, I want to make it so we only consider paths that you can actually do in the game. If the game only lets you enter a grass patch from one tile, then I also want to assume we can only find a path from that one tile.

The following sections are going to talk a bit about the concepts behind figuring out whether a patch is solvable or not. The goal isn't to derive a formula from nothing, but to build intuition to judge a graph's solvability quickly. If you want to skip the conceptual stuff to get to the routes, click here!

Breaking graphs into smaller graphs

One of the reasons I wanted to look at this topic was to figure out if there were any principles that would help us find if a graph was solvable without having to brute-force it. There isn't a one-size-fits-all way to figure out ahead of time if a graph is solvable or not. Since I'm not reading the literature, I wouldn't know about it anyway. How can we get started on asking the question about what principles would let us know if a graph is solvable or not? I decided to begin investigating by looking at very small graphs.

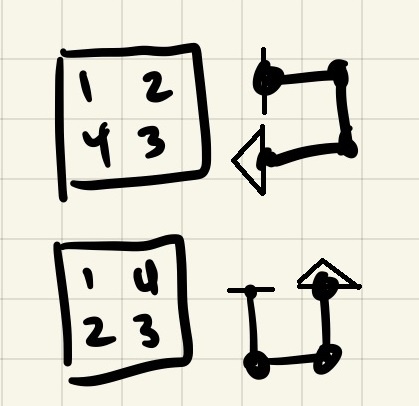

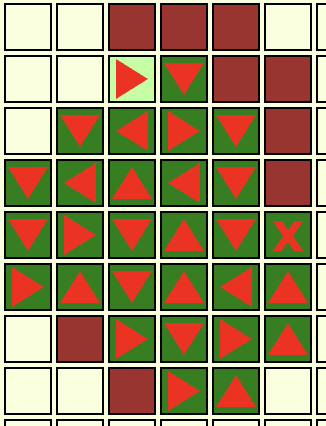

2x2 graph

Let's start with a 2x2 grass patch. We can easily list all the solutions. Noticeably, if you enter a 2x2 graph on the northwestern tile, you will exit either by the northeastern tile or the southwest side. There is no way to exit on the southeastern tile. If you enter a 2x2 grass patch, you cannot exit through the tile diagonal from the one you entered from. It's almost like a direction-reverser!

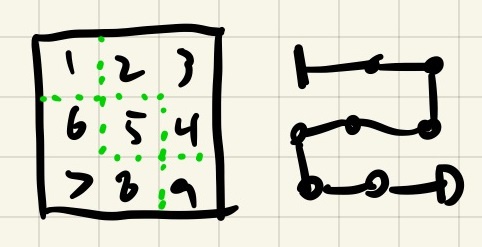

3x3 graph

I then looked at 3x3 graphs. If we start at the northwest tile, we can see that there are a few possible exits. You can start at the northwest and come out the southwest, northeast, southeast, and center. You can't come out the center-east, center-north, center-south, or center-west. If you want to solve this graph, you need to come out one of the corners or end up at the center. You can't actually solve this graph if you start at any of the edge-middle directions!

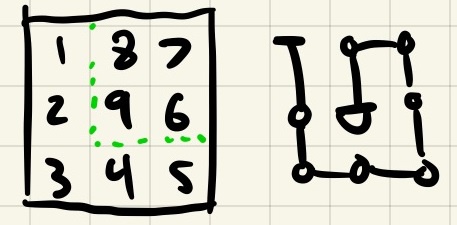

Very cool, but why does this matter? Well, it turns out if you take two solvable graphs and join them so there is no overlap and the exit of one is the entry of another, the result is a bigger graph that is also solvable! This suggests another property of solvable graphs: they are made up of smaller subgraphs that are joined together at "ports" (entry/exit points).

This also leads us to another realization: if all that matters to create a solvable subgraph is whether you can line up the exit/entry points, the interior path you can take to get there doesn't really matter. The entries and exits are the most important thing.

Looking at our 3x3 graphs, we can see that most of the ports at the corners. If we want to 'tile' a graph with these 3x3 graphs, we're going to mostly moving from the corner of one 3x3 graph to another. Additionally, the situation where you exit at center is only useful if that is the very final node left to visit, as otherwise you would have to backtrack to exit.

Knowing this is pretty useful - we can look at a graph and imagine trying to break it into chunks with the puzzle pieces we have.

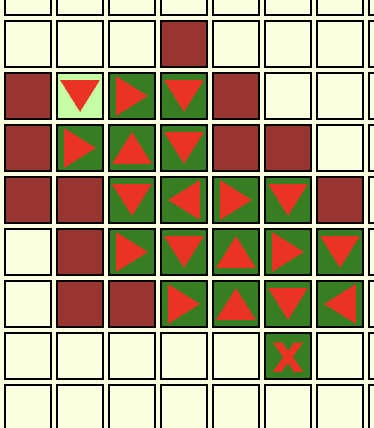

Quick Tests

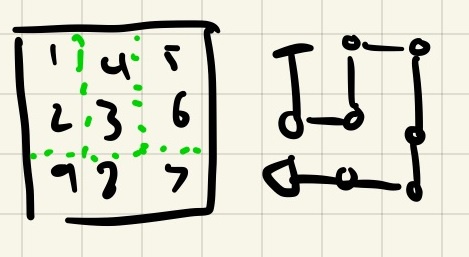

One of the core issues behind unsolvable shapes is that choosing one path prevents you from filling in a tile, but choosing a different path prevents you from filling in a different tile.

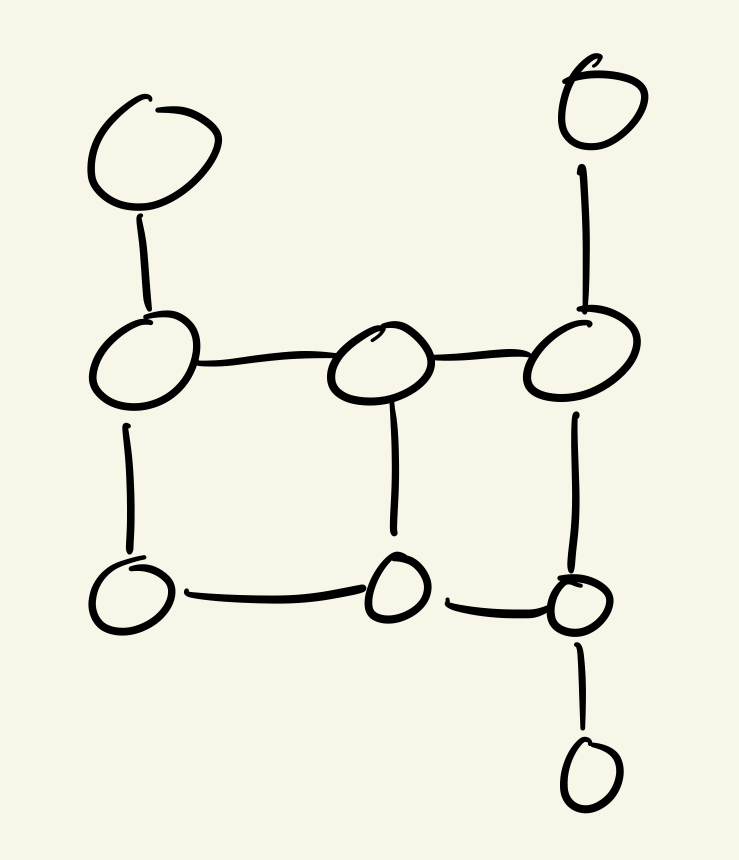

The simplest version of this is the T-shape. No matter where you start on the t, there is no way for you to fill every tile. Picking one will force you towards an end that does not allow you to circle back and get the missing one.

Remember what we said above about how solvable graphs are made up of smaller solvable graphs joined together at the ports? Think of the solvable graphs we have. There is no way to join them together to make a T.

Now, just because a graph contains a T shape does not mean that it is necessarily unsolvable. For example, the following graph contains that T shape but is actually solvable because the T is a result of other shapes.

Nevertheless, it is good to keep an eye out for graphs that contain known unsolvable shapes, as these can be worrisome.

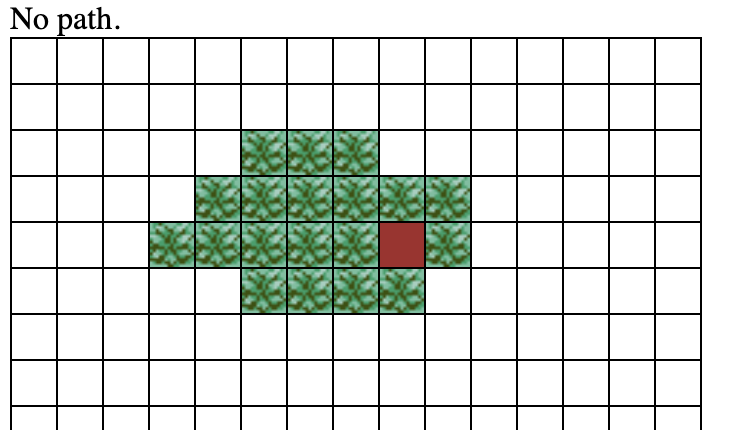

One of the easiest ways to know that a patch is unsolvable is if it contains more than two tiles that only have one connection. If a tile has only one connection, then that means that to be stepped on, it must be either the first or the last tile visited, as entering it means cutting off any further possibility to progress. If there are three, one of those tiles will always be skipped, as there is only ever one end and one beginning.

Even if a graph has only one or two tiles with a single connection, you must be wary of those because they limit the possibilities. If you have a single 1-edge tile, that means your path must start or end on that tile. If you have two 1-edge tiles, your path must start and end on those tiles. This can become a problem if this forces you into taking certain internal paths.

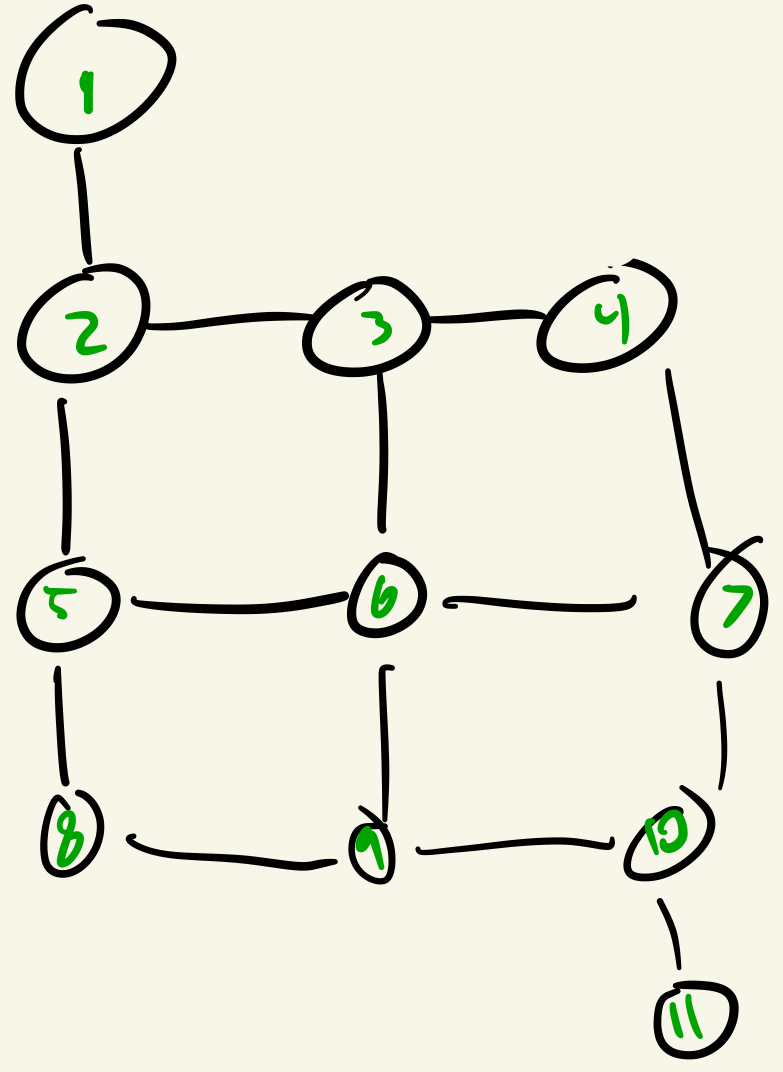

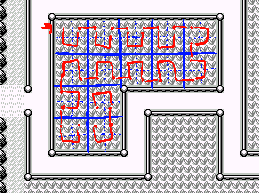

Enough abstraction. Let us try solving some patches to see what problems we run into. When we start a patch, it is useful to note the possible entries.

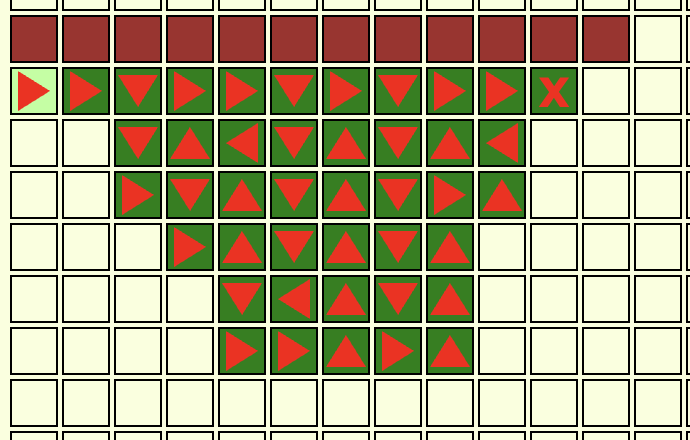

This one from route 115 is quite illustrative. Assume we can only enter through the bottom two tiles. Let’s say we want to get all the tiles on the right hand before we cover the left. If we try to do a serpentine pattern, we will find that the fact we have an odd number of rows means that our path will be tossed to the right - not the correct solution!

What if we try to hug the outline instead? This creates a problem. As you walk through tiles, you also affect the remaining tiles by removing potential connections. In this case, this creates a problem: we create multiple tiles that only have 1 connection left! (All marked in yellow rings.) This is a problem because as we noted earlier, you must enter or exit through a one-degree patch. But we did not enter through that patch of grass. This means we must end there. But we cannot end there because there is another one degree tile at the bottom. This means fulfilling both is mutually exclusive. The outline path won’t work.

Here are some rules of thumb:

- If there are more than 2 tiles that have 1 connection, the graph is unsolvable

- If there is 1 tile that has 1 connection, the graph must start or end at that tile

- If there are 2 tiles with 1 connection each, the graph must start and end at both tiles

- Outlining is dangerous because it can create smaller graphs with many 1-degree connections

- Misaligned rectangles are dangerous - diagonals are trouble

The routes

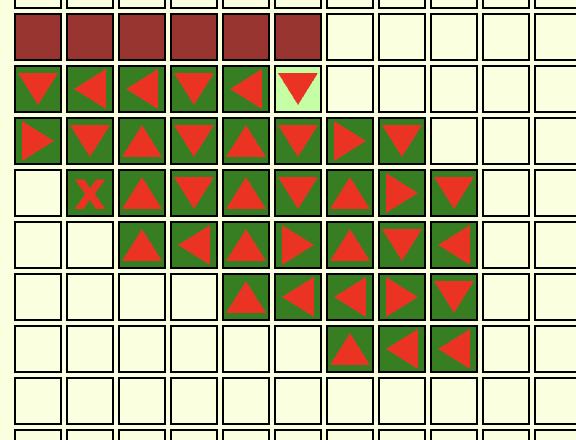

Let's actually look at the routes and take a crack at solving them. I sat down and went through all the routes in Emerald and tried to find a solution for them. (I ignored some very large ones like the ones on Cycling Road, and I also ignored areas like Petalburg Woods. Routes only!) Trying this out by hand showed me some interesting patterns about what made a route solvable or not. I also made a tool to confirm that a given patch did or did not have any solutions to make sure I wasn't missing anything myself - if you see a table with a bunch of filled in tiles, that's the tool! With that cleared up, let's go route by route and see how it goes.

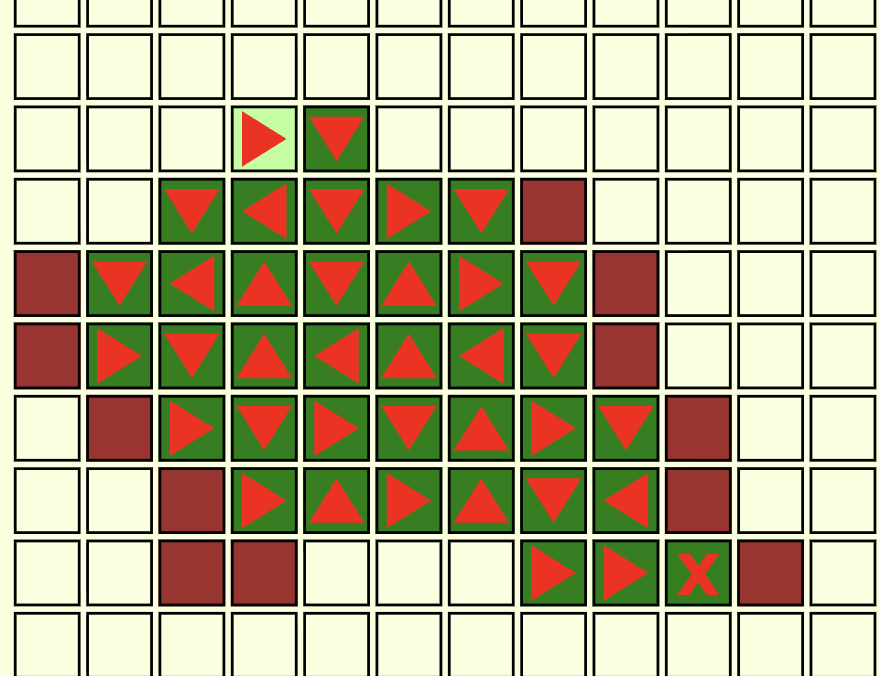

Route 101

Most of this route is solvable! That one on the bottom right is tricky. It has relatively few entry points, but even if you ignored those, it's just not possible to get all of them. Having so many of those tiles that stick out becomes a problem.

3/4 = 75%

Route 102

Half of these are solvable. You can see in the big diagonal-looking one in the middle that I marked the diagonals as problem areas. Diagonal edges are basically tiles that have only two connections to other tiles. This means that while you're trying to solve them, it's really easy to step on one of the connections for those outer tiles and accidentally turn them into one-connection tiles... which is very problematic for reasons we'll discuss later.

The awkward little path in the middle looks as if it's made up of little squares, which means it should be easy to do, right? Only it is not made up of little squares. We're forced to start at the tile on the right because that one has only one connection, so a successful path has to cross that point. But no matter how you do it, you will always have one left over.

3/6 = 50%

Route 103

100% solvable! You can see clearly here with the light green lines how you can turn the graph into chunks that meet up with each other, like a puzzle. You can see that these successful graphs are basically rectangles that are linked together with the occasion two-tile line or single tile used to pivot or enter.

3/3 = 100%

Route 104

South

The southern part of this route is entirely solvable! The easiest one is that one right near the entrance that is just a 2x4 grid with an extra tile right at the end. The one on the left shows you can have a pretty sprawling graph and still solve it, so long as it's made up of aligned rectangles.

3/3 = 100%

North

We know right off the bat that this is unsolvable because there are multiple tiles that are only connected to one other tile. And that's if you ignore the tiles that aren't even connected to any other tiles, crossed off in black at the top. The holes in the middle of the patch don't help, either. Not a very nice graph.

0/1 = 0%

Total = 3/4 = 75%

Route 115

This is one where you can see off the bat that the only possible solutions are not really gonna work together. Imagine going in from either of the two bottom tiles. You don't want to cross over into the tile right on top of the other entrance tile because then you block the path to that one. So you keep trying to go upwards... but then you end up facing the wall. Trying to go north in a snake-like manner is a problem here because the serpentine maneuver is basically a bunch of 2x2 graphs stacked on top of each other. And if you remember what we said, 2x2 graphs reverse the direction you were going in. So we're forced into the wall.

You might wonder about not starting on those bottom tiles, but trust me, this one is unsolvable.

0/1 = 0%

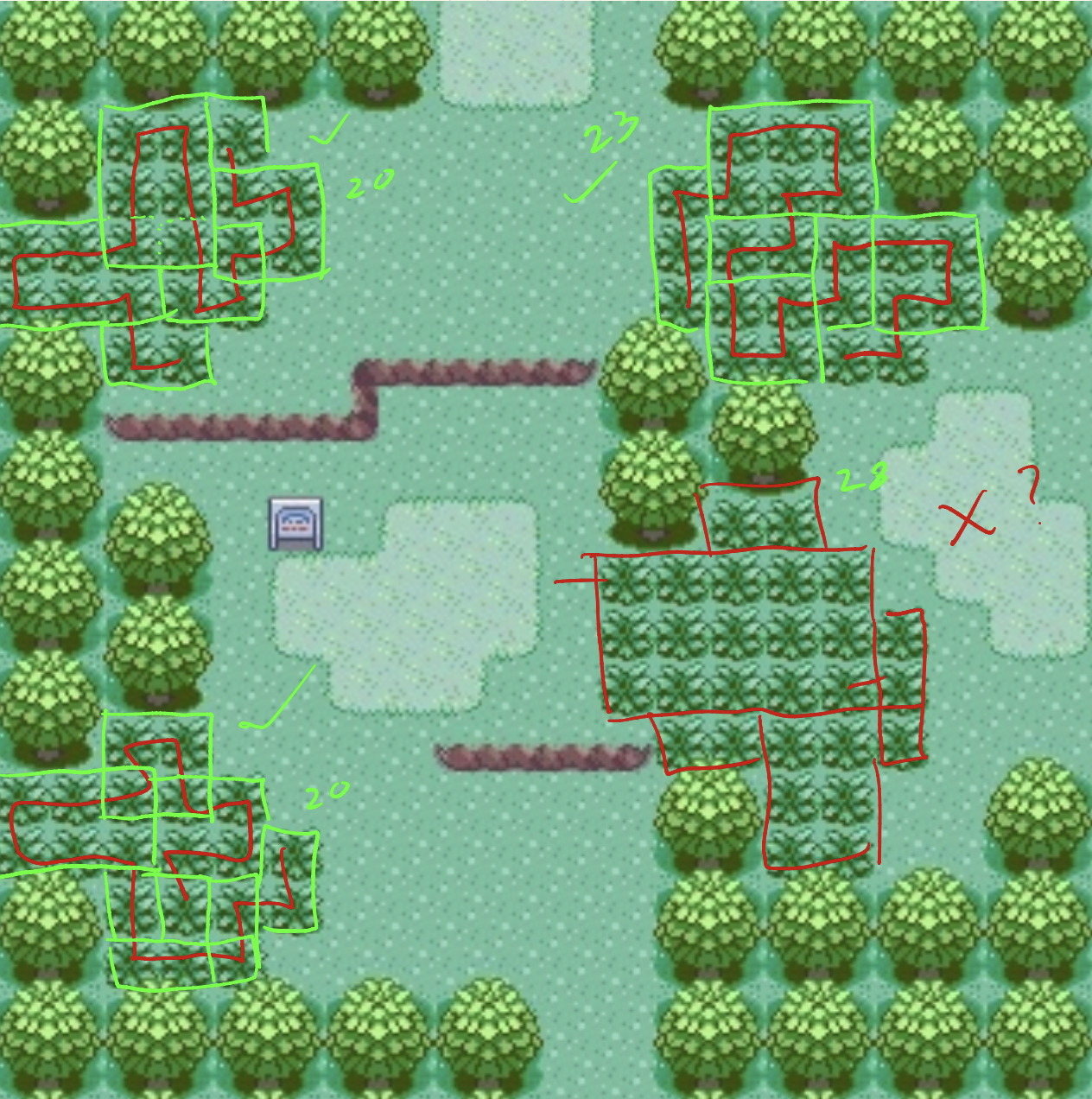

Route 116

That t-shape in the bottom-right one disqualifies it right away. The three one-degree tiles in the bottom-left one also disqualify it. The top-left one also has three one-degree tiles (which I somehow missed when first trying to solve).

0/3 = 0%

Route 117

The one on the bottom right actually has hidden grass tiles that I missed when I was first working through these. Alas, that does not save it, as it is still unsolvable as confirmed by my tool.

2/3 = 66.6%

Route 110

Not touching the cycling path!! Sorry! Too big!

0/1 = 0%

Route 112

North

They are both unsolvable, although I missed the hidden grass tiles on the bottom one.

0/3 = 0%

South

This one looks like it should be solvable. It looks like rectangles next to each other! But you can see a major issue: the corner of the 3x3 section on the right hand is not aligned with the exit of the 5x3 rectangle! And so we are forced to enter through an entrance we know will not hit every tile.

0/1 = 0%

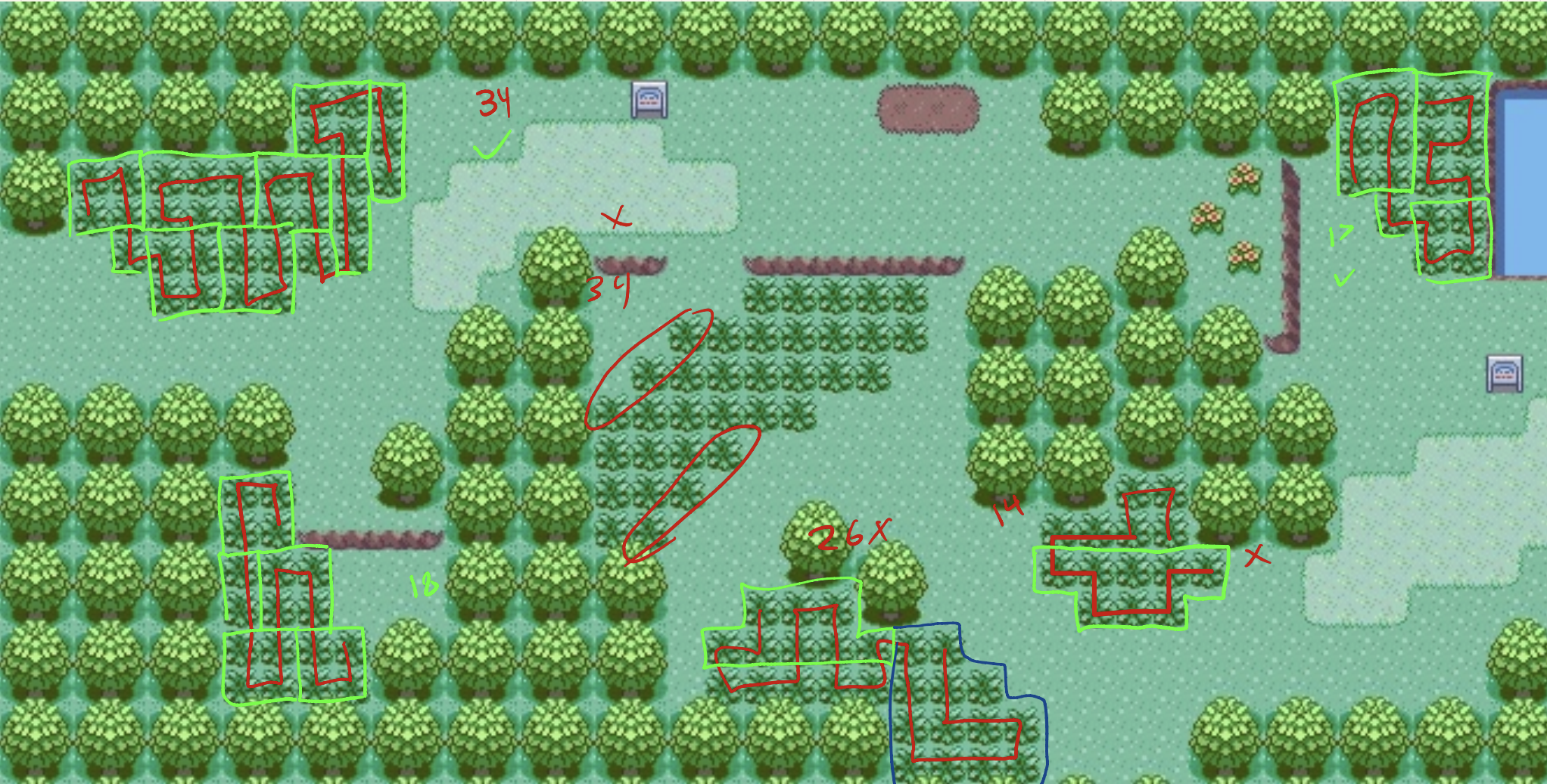

Route 113

Ah, the route that sparked my curiosity. So 1 of them is certainly solvable, and 1 I feel confident is not. What about the middle one and the far right one? My horrible algorithm actually hangs trying to solve the middle one, which leads me to believe that there are not any solutions for it. My vibes tell me that the one on the far right is also not solvable.

1/4 = 25%

Route 114

The middle one here has a T-shape, so we can't really solve it.

0/3 = 0%

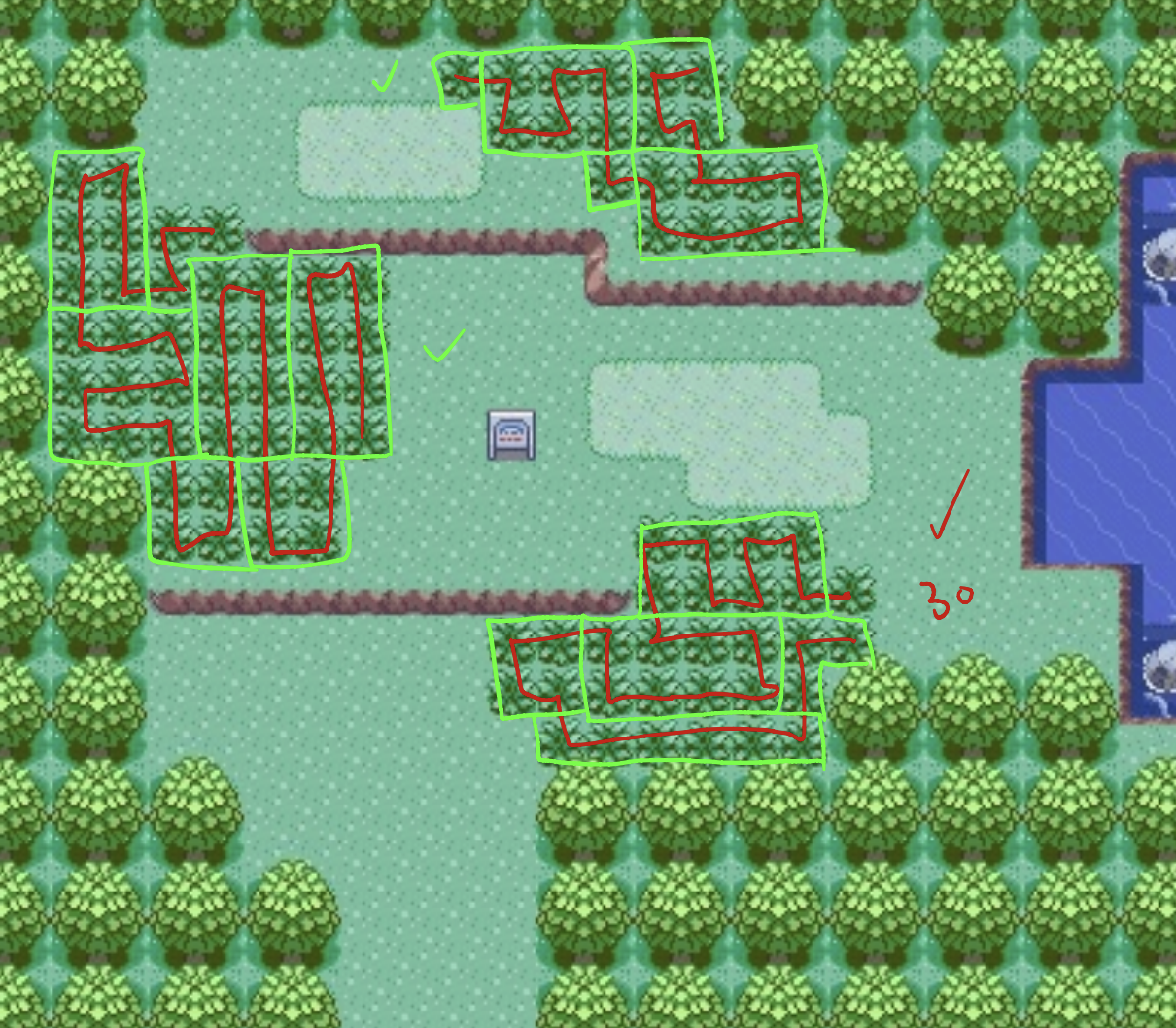

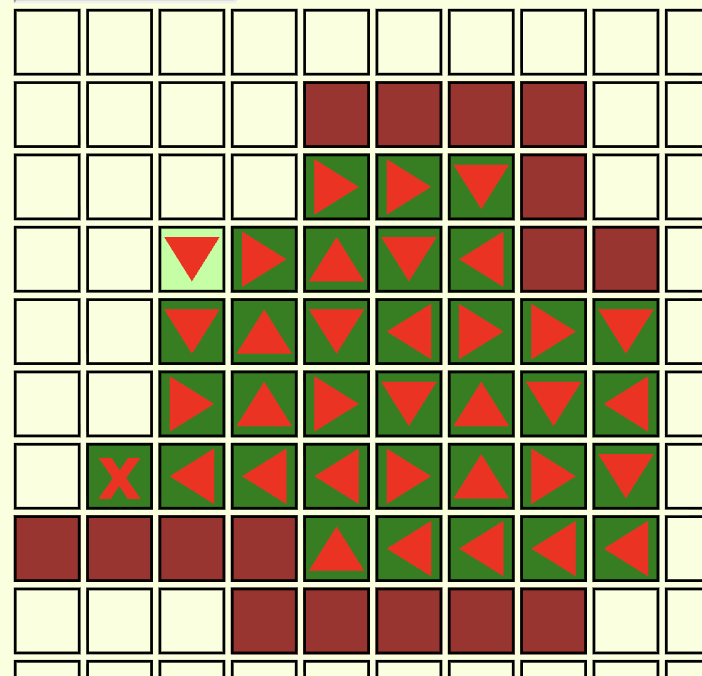

Route 118

You'll notice that I marked the bottom-right one as not solvable, but that is because I was missing some hidden tiles. If you include those peeking out from beneath the tree-tops, it is in fact solvable.

I had also missed some tiles on the bottom-left one, but it is still solvable.

4/4 = 100%

Route 121

5/9 solvable

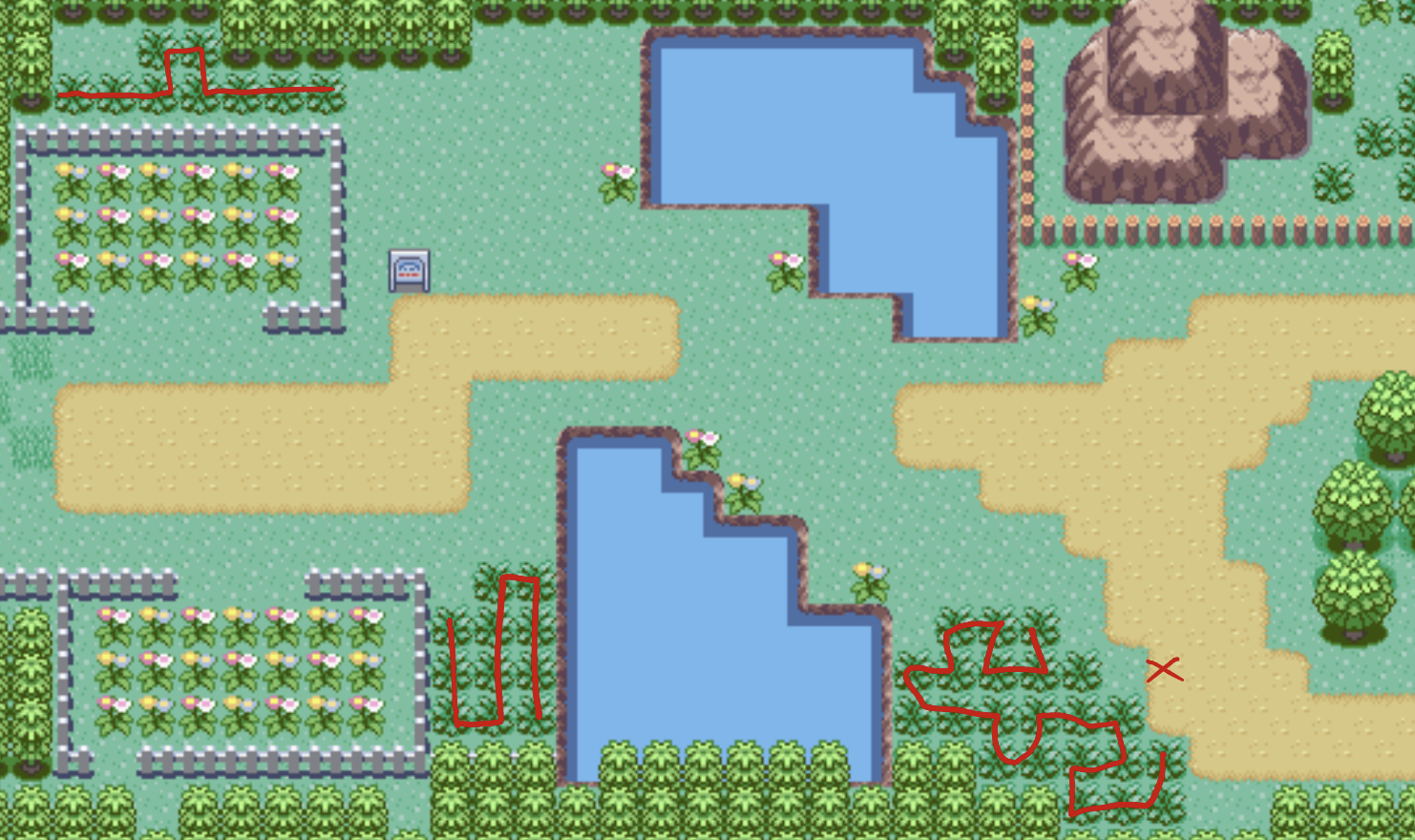

Route 123

From left to right:

Far left had hidden tiles. Solvable.

Top left had no hidden tiles is solvable.

Below top left is solvable.

Top center of the screen is solvable.

Second from the right is solvable.

Far right is solvable.

6/6=100%

Conclusions

So, what percentage of patches of grass in Emerald routes are solvable? 30/55 = 54.5%! About half the tiles on the routes (excluding the big ones on cycling road) are solvable! You have a coin's flip chance of solving any grass patch you come across on a route.

There are configurations that we know would cause unsolvable paths that we don’t see in this game, likely because they would make for ugly-looking patches of grass. For example, we could have two triangular shaped patches connected by a single patch of grass. The forced movement through that middle tile prevents finishing both patches. But how ugly would that be! The game designers clearly wanted natural looking patches of grass, which means grabbing that paint tool and just making blocks of grass. By accident, they ended up making many solvable graphs.

R/B/Y Aside

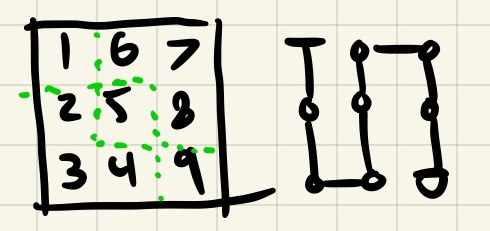

Fun fact - in Pokemon R/B/Y, the smallest unit you can use to tile the world is 4x4 player-sized tiles. The only grass tiles, to my knowledge, are fully filled 4x4. This means that every patch of grass is made by tiling together these 4x4 squares. These 4x4 squares are aligned edge to edge.

Why does this matter? Remember the 2x2 subgraphs we discussed above. When you enter a subgraph through one corner, the available exits are through the corner left/right to it and the corner above/below it. This means if you chain these subgraphs together, every exit will always be next to a potential entry, no matter the shape.

Because of the tiling restrictions, R/B/Y are 100% solvable! 🙂